Drink if you’ve heard this before: the Minnesota Wild have a penalty-killing problem.

It wasn’t always like this. Before the 2020s, the Wild were synonymous with good shorthanded play. It made sense, given their staunch defensive reputation, which has returned in the 2024-25 season. Strangely, the penalty kill has not followed suit.

It seems that enough is finally enough. John Hynes has changed the penalty kill system.

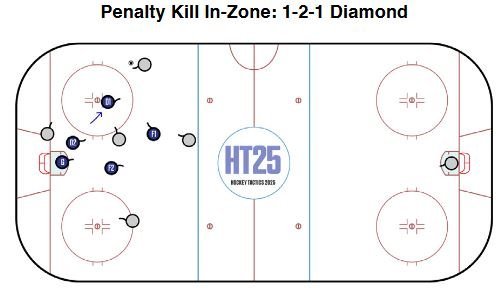

The Wild ran a 1-2-1 diamond at the start of the year. Jack Han identified a 1-2-1 diamond in his book Hockey Tactics 2025. It’s the same system that Minnesota ran in the previous two seasons, as Han identifies in earlier versions of the book.

Under this system, one defenseman covers the net front, and the other three players fill out the rest of a diamond shape in their own zone. By defending the net front with the weak-side defenseman, the strong-side defenseman is free to attack the puck carrier. It can be extremely effective when that strong-side defender creates turnovers, which they can clear to the other end of the ice.

Any four-on-five defensive scheme will have holes. The hole in this system is that it leaves the weak side of the ice open to a dangerous pass. The penalty killers are betting they can force a turnover before the puck carrier can thread a pass to the opposite side of the ice. Call it the Diamond Gambit.

When the gambit fails, it looks like this.

Notice that Freddy Gaudreau and Marcus Foligno are in a passing lane, but there’s still a dangerous shot available to Seth Jones from the point.

Part of the issue is that Bogosian retreats to the net front rather than attacking the puck carrier, which gives Connor Bedard time and space to find Jones. However, it’s theoretically possible for Bedard to find that pass even if Bogosian applies pressure correctly.

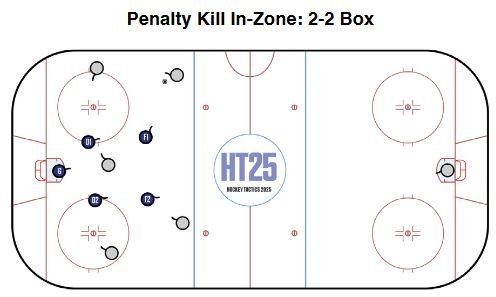

The benefit of this system is that it pairs well with an aggressive box, which Minnesota uses when their opponent has three players at the blue line. It allows their PK forwards to apply pressure when the puck is high in the zone, potentially creating a turnover.

The 2-2 box has largely been solved since the advent of the 1-3-1 power play shape. It works great in your beer league, but the passing skill of the modern NHL, combined with the 1-3-1 spacing, renders it ineffective.

That’s why the Wild combine this with a diamond system. If the opponent successfully works the puck deep into Minnesota’s zone, they shift to the diamond. That frees Minnesota’s strong-side defenseman to pressure as well. It’s all pressure, all the time.

That scheme aligns with Hynes’s vision for the penalty kill. He wants to stop entries whenever possible and create turnovers at all costs. When successful, the opposing power play won’t ever generate chances because they’ll spend the full two minutes trying to enter Minnesota’s zone and set up their shape. It’s the best route to an elite penalty kill.

The trouble is that it hasn’t worked for the past two years. The Wild’s PK ranked 30th in the NHL last year with a 74.5% kill, and they’re worse this year at 71.3%. The main culprit is high-danger chances. Last year, Minnesota ranked 26th in high-danger 4-on-5 goals against per-two minutes. This year, they’re 31st.

Even worse, the Wild rank 27th in shorthanded shot attempts against. The entire point of the diamond is to prevent shots from happening anywhere in their zone, and they have not enjoyed that benefit in the current system.

Hynes’s penalty-killers must walk before they can run. Rather than trying to return to their elite PK form of 2022-23, getting back to average would be a major step in the right direction.

Therefore, Hynes appears to have implemented a 1-1-2 penalty kill structure to serve that goal. This can also be called a “wedge-plus-one” because of the wedge shape created in front of the net.

This system is specifically designed to challenge high-danger passes. In a 1-3-1, the most dangerous plays come from the flankers, pictured above as the gray players near the faceoff circles. One such example happened in the Los Angeles Kings game.

That’s a bad example of how to execute the wedge-plus-one, but it shows the staple play of a 1-3-1: a pass from one flanker to another.

Let’s look at a better rep against the Utah Hockey Club. Notice how early in the video, both defensemen are in position to block a shot from the flanker. Gaudreau, the forward playing the “point” of the wedge, is in position to deny cross-seam passes.

You can see Gaudreau turn his head to check on Utah’s weak-side flanker. He then turns his eyes toward the puck carrier, planting himself and his stick in the passing lane.

The Diamond leaves the weak side of the ice poorly defended. Instead, this system has two players, Gaudreau and Brock Faber, defending their opponent’s most dangerous play. The high forward — in this case, Yakov Trenin — applies pressure to the puck carrier and defends the passing lane back to the point. That avoids opportunities like Seth Jones’ goal in

Chicago. However, the wedge-plus-one’s pitfall is on display against Utah. It doesn’t create effective pressure as often as the box or diamond. Brodin can’t sit in the shooting lane and pressure Hayton simultaneously, and the same goes for Faber.

The Pittsburgh Penguins power play had success from the same area.

However, the Wild will likely improve their ability to execute a new system over the final games of the season, which should reduce plays like this. Hynes didn’t implement a penalty kill with an Achilles heel that would allow the opponent to walk through the slot. As Minnesota’s defense corps gets healthier and the players get more comfortable with the system, they can execute it better.

That’s not a guarantee. Implementing a new system outside of training camp is challenging, especially for a team that rarely practices and is already fatigued due to a season-long injury streak. If the players can’t adopt the nuances of this new system, it could be even leakier than the diamond.

Still, the benefits of a league-average penalty kill would be significant. If the Wild continue to take about 2.5 penalties per game, but they improve their PK from 71.3% to a league-average 78.4%, that projects to an extra 1.25 penalty kills over a seven-game stretch.

In other words, it could be enough for one goal per playoff series.

The Western Conference playoff picture is stacked with elite power play units. The Winnipeg Jets’ power play ranks 1st in the NHL, followed closely by the Vegas Golden Knights (2nd) and Edmonton Oilers (6th). One of those three will most likely be Minnesota’s first-round opponent. Entering those series with a bottom-five penalty kill would lead to a quick exit.

Hynes is betting that the Wild can establish this systems change before those teams come to town. Call it the Wedge Gambit. I like it better than the Diamond one.